I had already learned to ride a bike with other children before I went to school, but I didn't get my first bike until I was almost nine years old, at Pentecost 1967. I actually wanted a 24-inch bike, like a friend of mine had, but the owner of the Sonnberger bicycle shop on Stresemannstraße in Bad Nauheim said that a 26-inch bike would be more suitable for me, as I would quickly grow into it. My father added that large wheels also had less rolling resistance than smaller ones and were better at handling uneven surfaces.

So I took the 26-inch bike I had my eye on for a test ride in front of the bike shop, and it was a done deal. My father paid 200 Deutschmarks for a Heidemann ‘Fürstenkrone’ bike with a Torpedo three-speed hub gear. I had chosen the colour red, which is why my father nicknamed it ‘Florian’, after the patron saint of firefighters. And so the bike had its name.

The ‘Florian’ was to accompany me for around ten years. Six years later, I discovered trials riding with it and also completed the sections of my first bike trials with it. It eventually ‘died’ due to a break in the lower frame tube just behind the head tube – where the torsional forces are strongest when pedalling hard. I wanted to have the frame welded, but at the time I couldn't find anyone who was willing to weld the frame!

There is not much to report about the years 1967-1970, except perhaps that I enjoyed riding along field and meadow paths from the very beginning. Due to my age, I soon developed a soft spot for racing cars – somehow I had come to that conclusion. When I saw posters for the hill climb race at the Schottenring in June 1971, I was determined to ride my bicycle there.  But my parents didn't want to let me drive 80 kilometres alone on the roads in one day at the age of twelve. The solution was to get a lift from friends.

But my parents didn't want to let me drive 80 kilometres alone on the roads in one day at the age of twelve. The solution was to get a lift from friends.

I remember being a little disappointed at missing out on my first big adventure of an extended bike tour, but at least I got to go to the hill climb race. The weather in Vogelsberg was mixed, but the racing atmosphere in Schotten was something special. It was there that I first noticed the motorcycles that were also part of the programme – I was particularly taken with the sidecars.

After that, it took three long months until September before I found another poster advertising a race. This time, they were advertising a motocross event in Hausen-Oes near Butzbach – only ten kilometres from where I lived! It was clear that I would go there with the ‘Florian’ and so I eagerly awaited the date. After the hill climb, I was as excited as could be to see what a motocross event would be like.

The mountainous forest course in Hausen-Oes, set in idyllic surroundings (now a nature reserve), was not cordoned off as extensively as the road race in Schotten, and spectators were right next to the track. The roar of the two-stroke engines, the dust and the chaos, heightened by the contrast to the harmless music blaring from the loudspeakers during the breaks – but also the independent journey there on my own bicycle – all this was just right for a thirteen-year-old who was setting out to conquer the world. Motocross had surpassed hill climb racing for me, and on the way home I vowed to go to every race I could reach by bike from then on. I hoped for more events in the coming weeks, but I couldn't find any more race posters – the 1971 season was obviously over by late September.

From then on, I read ‘Das MOTORRAD’ – also to find out about event dates. That was where I first came across the word ‘trial’, although I didn't know what it meant. The occasional reports about it raised more questions than they answered. The track looked interesting in the photos – but (at that time) riders rode without helmets, wearing only some kind of caps, and strangely standing up. Speed didn't seem to matter! There were some kind of points, but it was mentioned positively when someone didn't get any – so penalty points? For what? I couldn't make head nor tail of it.

I bought the ‘MOTORRAD Catalogue 1971/72’ because of the many photos and the overview it provided. I found the competition models for the individual disciplines most interesting. I also found the trials bikes pictured appealing and interesting, but the accompanying captions didn't help me: ‘Special model for trials use. Tailored engine characteristics and gear ratio’ – what was I supposed to make of that? Trial remained a big mystery to me in motorcycling, and I didn't even know whether it was pronounced in German or English.

In 1972, I attended a total of nine motorsport events covering all kinds of disciplines. By then, I had also infected some of my friends with my enthusiasm, which resulted in carpooling trips to the Nürburgring (today's Nordschleife) for the 1000-kilometre race and the Formula 1 Grand Prix. Another highlight was the 500cc Moto Cross World Championship race in Beuern (there is a photo of this under point 4 in the chapter ‘The Seventies’), which was bursting at the seams with spectators. I almost liked the small Moto Cross in Lang Göns a week earlier better because of this. But I hadn't been taken there, I had ridden there on the ‘Florian’ and enjoyed the new feeling of independence and freedom. All in all, it was a great year. I had now seen all disciplines – except trials. So my mystery remained and made me more and more curious.

‘Trials riding – but how?’ – a series of articles in MOTORRAD magazine 1

In the summer of 1972, it was already clear that this year would end without a trial for me. The article ‘Trials riding – but how?’ published in MOTORRAD in August provided the explanation: "Trials riding is not at home in all areas of the Federal Republic. There are certain areas where it is more popular" 2 I read there – my area around Bad Nauheim was obviously not one of them.

In the second part of the article ‘Trials riding – but how’ in MOTORRAD magazine dated 26 August 1972, there was a photo showing a child on a moped beneath a picture of Sammy Miller, who was unknown to me at the time! 3

I can still remember how the photo affected not only me, but also a classmate whom I had infected with my enthusiasm for motorcycling and with whom I rode my bike to motocross, grass track and hill climb races in the area for a while. His name was Manfred Barth – two years later, he was also an observer at my first bicycle trial in Section 3 (get in touch if you're reading this!). We puzzled over trials together and, after school that Saturday, we bought the new issue of ‘Das MOTORRAD’ magazine, which we eagerly awaited every other Saturday, at the station bookshop in Bad Nauheim.

When we saw the photo of the child on the moped, we both laughed at first, and then we were horrified. The explanatory text accompanying the picture read: ‘Mopeds are only suitable for trial riding to a limited extent, but you can learn how to ride early on!’ – but still: was this supposed to be trials riding, a serious motorcycling sport? At the time, I defiantly thought to myself that you could probably do trials with a bicycle just as well as with a moped – no, even better! My friend wasn't particularly interested in this – he was more enthusiastic about the motorcycles than the riding. In contrast, my existing curiosity about trials was further piqued by the prospect that trials would probably be very easy to do on a bicycle. After all, I tried everything I saw in the races on my bicycle – I'll come back to that later.

The third part of ‘Trials Riding – But How’ in the next issue of MOTORRAD two weeks later, which appeared on 9 September 1972, presented a few trials bikes that I already knew from the MOTORRAD catalogue – but that wasn't important to me at the time. However, under the article, I suddenly and completely unexpectedly discovered an announcement for a small trial in Aßlar near Wetzlar, which was already taking place on 10 September, i.e. the very next day! Aßlar was 35 km away from me, so within reach with the ‘Florian’. I hadn't driven in that direction before, but that's what road maps are for. The problem was that this sudden trial clashed with an upcoming family birthday.

Accordingly, this time I encountered less understanding for my entrepreneurial spirit. My mother said, ‘You've already been to so many races this year, in Beuern and even at the Nürburgring!’ My objection that I had never seen a trial before and now one was finally taking place within reach made no impression: "There will be another trial again! We would finally be all together again! " I wasn't forbidden to go, that wasn't how we did things, but at fourteen I couldn't cope with the moral pressure of being a spoilsport. So, with a heavy heart, I gave in, taking some small comfort from the fact that I wouldn't have been able to buy any film cassettes for my Kodak Instamatic at such short notice anyway, because it was already Saturday afternoon and the shops were closed.4

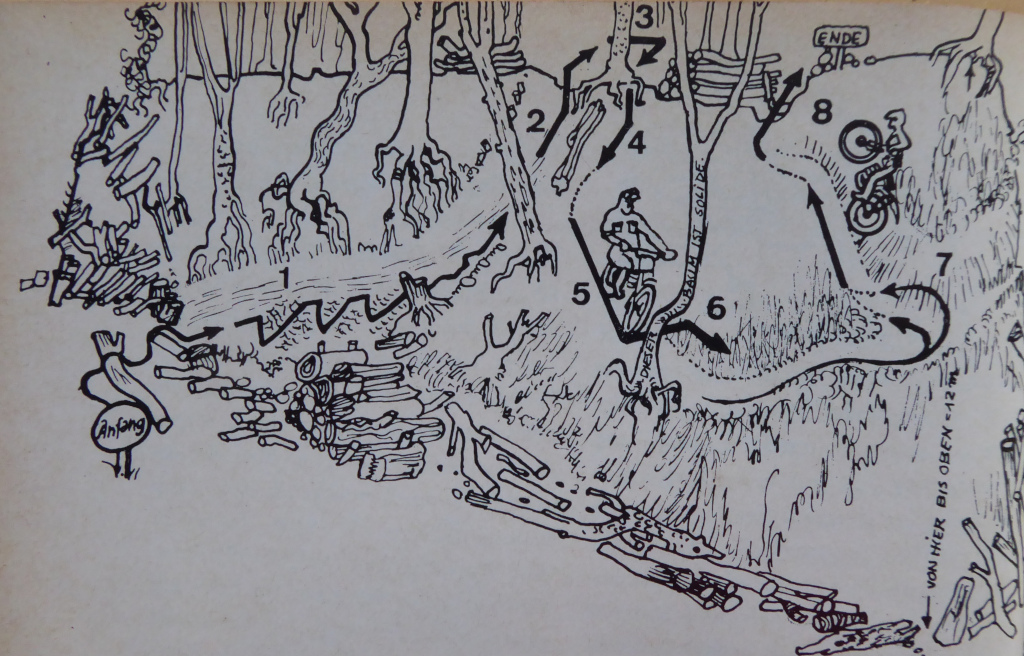

The fourth part of the article ‘Trials riding – but how?’ at the end of September 1972 focused on the technical details of trials motorcycles. The announced fifth and final part was then missing from the next issue for unknown reasons. It appeared, when I was no longer expecting it, after three months in MOTORRAD on 30 December 1972.  The surprising and interesting thing about this last part of the article was the sketches it contained, along with Crius' accompanying explanatory texts, which explained specific situations in trials in a way that was both funny and educational.5 The explanatory text for sketch 1, for example, read: ‘Sometimes a bold burst of throttle can prevent you from going over the handlebars on a step like this,’ and sketch 2 read: ‘Small jumps like this are quite nice for the spectators, but you should check where you're going to land first – maybe with the front wheel in a pothole?’ This was trials riding at its most accessible and left us wanting more – more trials riding and more Crius! The book ‘Sport mit Motorrädern’ (Motorcycle Sport) now rose in my estimation – or rather, in our estimation, because my classmate also loved the sketches and, infected by my enthusiasm for the book, later bought ‘Crius’ for himself as well...

The surprising and interesting thing about this last part of the article was the sketches it contained, along with Crius' accompanying explanatory texts, which explained specific situations in trials in a way that was both funny and educational.5 The explanatory text for sketch 1, for example, read: ‘Sometimes a bold burst of throttle can prevent you from going over the handlebars on a step like this,’ and sketch 2 read: ‘Small jumps like this are quite nice for the spectators, but you should check where you're going to land first – maybe with the front wheel in a pothole?’ This was trials riding at its most accessible and left us wanting more – more trials riding and more Crius! The book ‘Sport mit Motorrädern’ (Motorcycle Sport) now rose in my estimation – or rather, in our estimation, because my classmate also loved the sketches and, infected by my enthusiasm for the book, later bought ‘Crius’ for himself as well...

The ‘Crius’

From June 1972 onwards, MOTORRAD magazine carried advertisements for the third edition of Crius' book ‘Sport mit Motorrädern’ (Motorcycle Sports) 6, whose real name was Christian Christophe (1903-1993). The subtitle ‘Trial Gelände Moto Cross Straßenrennen’ (Trials Enduro Motocross Road Racing) 7 caught my eye because the book promised to solve my trials puzzle. Since then, I had kept ‘Crius’, as I had always called the book, in the back of my mind.

Nevertheless, I didn't buy the book straight away. At first, I hoped that there might be a trial somewhere within reach where I could get an idea of what it was like for myself. From August 1972 onwards, there was a series of articles entitled ‘Trials riding – but how’ in MOTORRAD magazine. However, I found that the information in the article was of little help to me, for the simple reason that it either did not apply to me or I could not understand it because I had never seen a trial before. In this respect, I was not particularly interested in additional abstract information from the new book.

Above all, the loud advertising for the book made me doubt whether it would deliver what it promised: "Who wants to ride motocross? Buy and read Crius' book ‘Sport mit Motorrädern’ (Motorcycle Sports) now! Crius also covers everything you need to know about trials, off-road and road racing. ‘Sport mit Motorrädern’ by Crius – absolutely brilliant! 8 In retrospect, I have the impression that this advertising not only put me off, but was also generally not particularly conducive to sales of the book.  In any case, at the end of October, Motorbuch-Verlag changed its advertising, which now promoted the book in a much more factual manner as ‘a novel textbook for sporting practice, interspersed with many interesting pictures and equally humorous sketches by the author’. 9

In any case, at the end of October, Motorbuch-Verlag changed its advertising, which now promoted the book in a much more factual manner as ‘a novel textbook for sporting practice, interspersed with many interesting pictures and equally humorous sketches by the author’. 9

Today, I think that against this backdrop, it was probably no coincidence that the last part of the article ‘Trials riding – but how’ at the end of 1972 was interspersed with ‘interesting and humorous sketches for sporting practice’ by Crius. This was probably intended to boost sales of his book, which had apparently fallen short of expectations due to clumsy advertising by the publisher. In any case, it worked for me. For me, the sketches and Crius' comments in the article meant that – at a time when I had firmly resolved not to let another year go by without seeing a trial – I suddenly realised that Crius' information about trials was not so abstract after all.

Only now did Crius become a ‘must have’ for me, as they certainly didn't say back then. That's why I bought the book – sometime in early 1973.

I immediately felt that Crius was a stroke of luck. The very first chapter was devoted to trials – and addressed precisely the question that was on my mind at the time: ‘What exactly is trials?’ The drawing reproduced here, which Crius used as an eye-catcher at the beginning of the chapter 10, almost anticipated the answer visually. It illustrated the technically precise riding on difficult terrain at comparatively low speeds that characterised trial riding and gave it its special atmosphere.

Crius had a gift for capturing what was important in just a few words – or with his sketches. Also on the first page of the trial chapter, he took a brief look back at the first Scott Trial in 1914 and wrote: ‘Perhaps that is why – because everything was so difficult – the moorland riders had already discovered the essence of the matter, which was: the game was much more than the player of the game – “the big game was the main thing, the players counted for far less”. We would like to recommend this as a guiding principle. It explains what sport should be.’ 11 It was only much later that I realised that what Crius emphasised right at the beginning was nothing other than the British trials philosophy, which focused on the section rather than the rider. 12

Crius did not write a textbook, but rather described the essence and atmosphere of the individual disciplines – especially trials riding. He not only had a talent for this as a writer and cartoonist, as I perceived it, but also the right perspective (the picture on the left of page 19 of my ‘Crius’ fits in well here), because as one of the less successful riders, he had tried pretty much everything out of a deep love for motorcycling and motorcycle racing. Most recently, he also tried trials, which he – born in 1903 – could only have discovered at an advanced age. I wasn't aware of this at the age of fourteen because I didn't know the history of trials riding at the time. 13

It was Crius that inspired me and got me into trials – I always kept the little book by my bedside and it was like a bible to me. Crius was a complementary read to my visits to races and inspired my own cycling activities. This applied to all disciplines (see ‘On the bike’ below), but especially to trials, which I found most exciting in the book because it was interesting, varied and appealing.

In addition, Crius unwittingly suggested bicycle trials in two places – I was alert to this at the time because I recreated what I experienced at my races at home on my bicycle. So here were indications that trials were feasible on a bicycle. The first instance was in the subchapter ‘A trial – from the handlebars ...’ (see also point 3 ‘Early bicycle trials’ with notes 8 and 9 there). 14, which stated: ‘With the momentum of the counter-slope (...) you certainly don't go back up again – even children on bicycles do that here – but along the slope, at speed, of course, so that the wheels don't slip individually or even both together.’ 15 – Who said you couldn't do the latter with a bicycle? Even back then, I assumed that Crius' remark was a stylistic device in the given context and not necessarily to be taken literally, but Crius had to have got the children with their bicycles from somewhere!

The second passage, shown opposite 16 – now somewhat yellowed – reflected the development in the 1960s whereby heavy four-stroke engines were increasingly being replaced by lighter two-stroke engines in trials. However, the popularity of small displacement engines was not only evident in trials riding, but was a more general trend in all forms of motorcycling and beyond. At the age of fourteen, I knew nothing of this background. 17 I simply thought through the process that Crius briefly described here: if the weight dropped, the balancing was no longer necessary and the enjoyable circling began... if that was what trials was all about, then bicycles must be ideal for trials riding! In any case, I found this passage encouraging.

However, despite all of Crius' sketches and explanations, I still lacked my own understanding of what a trial actually involved, and so it took a while before the penny dropped. In addition to my cycling activities (I will come back to this below under ‘On the bike’) – at that time mainly ‘motocross’ and ‘road racing’ – I had now added ‘trials’ to the list, but that was basically just riding over obstacles, steep slopes, roots and embankments, which I might or might not manage, but not yet a real trial with sections. My initial trials activities in early 1973 were more in line with what was then called ‘off-road’ and is now called ‘enduro’: this was influenced by Crius' description of the 1914 Scott Trial, which was about ‘reaching one point in nature from another in the most rational way possible. The route could be: fields, farmland, rocky ground, chamois trails, dilapidated tracks that were no longer used by hunters, fishermen, shepherds or mountaineers – just a line drawn on the map ... racing across streams and moors.’ 18 These were wonderful trips with the ‘Florian’ in the forests of the Taunus – sometimes for miles along the Limes, on a beaten path around trees and with many roots – which also met my age-appropriate need to discover new horizons.

The FAHRERLAGER (The Driver`s Pit)

I wrote earlier that I ordered ‘Crius’ from the bookshop in early 1973 and that it was this little book that infected me with the trials bug. I was finally going to attend a trials event – I wasn't going to let another year go by without seeing a trial!

Now was the time to remember a tip in the article ‘Trials riding – but how’, which I had wisely marked with a note between the pages of the relevant MOTORRAD magazine. It said that not MOTORRAD, but the newsletter FAHRERLAGER published by the German Trial Sports Association (DTSG) contained ‘practically all dates (of trial events), well in advance’. 19 However, it also stated that ‘depending on the availability of the volunteer editors, an average of five to six issues per year’ would be published. I showed this to my father, who

prompted the comment: ‘That can't really be anything important.’ It was probably his suggestion that I only have a sample copy sent to me first.

The FAHRERLAGER was indeed nothing ‘big’. It consisted of pages typed on a typewriter, hectographed and stapled together. The photo on the cover was often only vaguely recognisable. Until 1972, the covers had even consisted solely of drawings that had been traced from photographs using carbon paper. 20 The first issues of FAHRERLAGER that I saw already had a photo on the cover that was at least somewhat recognisable. However, the poor quality of the magazines did not detract from the overall appeal – quite the contrary: together with the irregular and uncertain publication schedule, this gave FAHRERLAGER a certain mystique and made it a magazine for those in the know.

However, it took forever for the requested sample copy to arrive. To be precise, there were two copies, issues 3/73 (March) and 4/73 (April) – which I finally received in May 1973. I remember the date so clearly because I learned from the two sample copies that there had been another trial in Aßlar a few weeks earlier, on 22 April 1973, which I had missed again! Unaware of this, I had taken my ‘Florian’ to the motocross in Gießen-Wieseck that weekend, only 15 kilometres from Aßlar ...

But what really caught my attention was the report on the ‘Trial in Mittelberg in Austria on 4 March 1973’ 21, which included a bicycle class in addition to a class for production motorcycles! 22

It is important to remember that the Crius had inspired my enthusiasm for trials and also gave me the impression that it was very feasible with bicycles. And now I suddenly read about a bicycle class at a trial in Mittelberg, Austria! Of course, like the production machine class, it was only an appendage to a ‘real’ trial, as the number of starters showed, but it had existed! The immediate effect of this news was that I now wondered how this trial must have actually gone. Only now did I come up with the idea of trying out the penalty point scoring system for trials, which had already been described in the MOTORRAD article ‘Trials riding – but how’ (in part 1) and explained by Crius with his characteristic brevity (see the illustration above belonging to note 16), in detail.

I can still remember clearly how, in May 1973, in glorious sunshine and surrounded by the delicate spring green of trees and bushes, I tried out the trials penalty point system in all its facets for the first time in the Frauenwald above the Frauenwald School in Nieder Mörlen. Using sticks or stones as markers at important points, I tried out different levels of difficulty, looking for an impossible turn that required a long foot and so on. Only then did the penny drop and I understood exactly how trials riding in sections worked. The lack of a freewheel was immediately noticeable. I also quickly realised that you could get through almost anywhere with a ‘three’. At that point, however, I hadn't yet come up with the idea that the penalty point system intended for heavy motorcycles was not suitable for light bicycles in this respect.

The variety of sections you could look for and try out was almost endless. This opened up a whole new and fascinating field of activity! What's more, with its slow pace, I felt that trials riding was a motorcycling discipline that could be easily transferred to cycling.

Of course, I subscribed to FAHRERLAGER, if only for the trial dates. I now wanted two things: to finally see my first trial and, above all, to take part in bicycle trials myself. However, neither of these wishes were to come true at first. It took forever, literally months, until the first regular issue of FAHRERLAGER finally arrived in September 1973! It was the September issue, 8/73. What can I say? Once again, I had to read that a trial had taken place shortly before, on 9 September 1973, in Aßlar, which I had now missed for the third time – it was like a curse! Slowly, I realised that the Aßlar trial took place on two fixed dates each year – the next one would be at Easter 1974...

I couldn't find the word ‘bicycle’ anywhere in this September issue, nor in the subsequent issues of FAHRERLAGER. The bicycle class in Mittelberg, which was reported on in the sample issue of FAHRERLAGER, was the only time that bicycles were mentioned in FAHRERLAGER until the article ‘Trialsport ohne Motor’ (Motorless Trial Sport) in the May/June 1975 issue (this article can be found under point 6 in the chapter ‘Ich lernte Pere Pi kennen’ (I Got to Know Pere Pi)). 23 So participating in bicycle trials didn't work out either, because they obviously didn't exist. The bicycle class in Mittelberg had therefore been an absolute exception.

The path to bike trials

I explained the lack of bike trial events by the fact that cycling clubs were unfamiliar with trials, while motorcycling clubs had no interest in bicycles. If a motorcycling club did include bicycles in its trials, it was as a ‘taster trial’ to attract young people to motorcycle trials – as in Mittelberg, where there was a standard machine class in addition to the bicycle class. In short, bike trials practically did not exist because they fell between two stools and were not taken seriously. Classes for mopeds, motorised bicycles and production motorcycles, on the other hand, did exist (at that time) in some regions, as I learned from FAHRERLAGER. But even these were, of course, only beginner classes to attract young talent to ‘real’ trials with specialised machines.

Now I wanted to organise my own bike trial event to fill this gap and prove that you could do proper trials with bicycles. A pure bike trial as an end in itself. One problem was finding observers, but that could be solved somehow with classmates and friends. Obtaining a permit should not be a problem with bicycles. But what about insurance? I did not have a club, and as a 15-year-old, I could not take out insurance for a bike trial! I was able to solve all the other problems, but I was stuck on this one point.

The November issue of FAHRERLAGER magazine had a surprise in store: "1-2-3-5: In England, they count differently..." was the headline of an article 24, which discussed the introduction of two points for two feet. The 1-3-5 system, which I had tried out and internalised as a trials scoring system six months earlier, had been changed! The argument that the introduction of two points was fairer and more appropriate for trials riding because it provided an incentive to continue riding in style and not to fall into foot-slogging even after a second foot had been placed was understandable and reasonable. It was now clear that my bike trial, which I couldn't get out of my head, would take place using this new scoring system from the beginning.

In December, my enthusiasm for trials was further fuelled. In FAHRERLAGER, Sven Kuuse presented a book by Sammy Miller: ‘Sammy Miller on Trials’. 25, which I ordered from Sammy Miller and received relatively quickly – autographed with ‘Best Wishes Sammy Miller’. Admittedly, Sammy Miller was no match for Crius in terms of style. But the book still fuelled my enthusiasm for trials because it created an atmospheric gateway to the motherland of trials. This was true in purely linguistic terms – my English also benefited from the English trials books that I gradually ordered when I heard about them in FAHRERLAGER.

But the photos also gave a good impression of the atmosphere at the British trials. Since I still hadn't seen a trial, I now wanted to see photos of the German trials as well. There were still about four months to go until the trial in Aßlar at Easter 1974 – the date of the first trial I would finally see was set in my mind. Classified ads were free for subscribers to FAHRERLAGER, so I placed a classified ad in the January 1974 issue.

In response, however, I did not receive any photos, but a phone call from Fritz Schneider, then chairman of MSC Dilltal in Aßlar, the only trials club in my area, whose events I had missed three times so far. Of course, the club was interested in attracting new members from the local area and had therefore responded to my advertisement. During this phone call, I was informed, among other things, that the traditional Easter trial in Aßlar would unfortunately have to be cancelled in 1974 due to an unfortunate clash with the German Trials Championship rounds in Mauer and Schatthausen!

Once again – for the fourth time now! – I couldn't go to the trial in Aßlar... Now I'd finally had enough. I studied the map: Mauer and Schatthausen were near Heidelberg, which is only about 150 kilometres from Bad Nauheim. Didn't my slightly older sister have a boyfriend with a VW Beetle? Wasn't Heidelberg a beautiful city? It didn't take much persuasion and the trip to Heidelberg was decided. The evening before the trial, we camped near Mauer and on Saturday, 13 April 1974, I was dropped off early at the starting point of the trial. While my sister and her boyfriend drove to beautiful Heidelberg, I was actually at my first trial, a German championship event!

The trial in Mauer in 1974

I was lucky with the first trial I saw – and first impressions are always formative. With the start and finish at a farmstead in Mönchzell near Mauer, I didn't linger long, but used the time before the start to cover the distance to the first sections so that I could be there early. It was glorious spring weather in beautiful countryside and I was excited about the sections. Sections 1-4 and 7 and 8 were located in a steep valley cut in the forest. There were two dry sections with earth slopes and four stream sections with steps, roots, and slippery approaches on the side slopes – wonderful sections that looked as if they had been cut out of the “Crius.” Since the remaining sections – two each in completely different locations – were far away according to the route map, I decided to spend the day at these six sections. 26

There was enough time to walk the sections. I looked for the lines I thought were most appropriate and was curious to see whether they would prove to be the right ones or whether the riders would take a different approach. I could hardly wait to see the first riders tackle these challenging sections. A short descent in section 2 was very steep and particularly tough. This was immediately followed by a tight turn, after which the ascent was steep again. This made it difficult to jump down the descent on the rear wheel – the technique of riding down and shifting position there before tackling the ascent had not yet been invented. Although there was a helpful rock on the left of the steep descent that could be used as a bridge for the front-wheel, the turn at the bottom was too tight and probably required a foot to turn. The further you rode on the outside, the more space you had at the bottom in the tight turn, but the steeper the descent became, as can be seen in the photo. But it worked, the rider didn't fall! – These were the issues in trials at the time: it was all about planning lines and finding successful compromises.

I was completely thrilled by the trial—even more so than by the trial the following day in nearby Schatthausen, which was also very nice, but the quarry just didn't have the atmosphere of the spectacular valley cut with its stream sections in the forest. I've always been sensitive to atmosphere and surroundings—or was Schatthausen already lacking the appeal of novelty, which is always unique?

Back in March of that year, I had noticed an advertisement in FAHRERLAGER magazine: Herbert Baume from MSC Fränkische Schweiz was selling marking tape in 500 m rolls for DM 11.80 each. 27 This naturally sparked my imagination with regard to the bicycle trial I had been carrying around with me for six months – especially at a time of anticipation for the trials in Mauer and Schatthausen and the start of the new season. Now, after the great trials in Mauer and Schatthausen, there was no stopping me.

At home, I raved about Mauer and once again complained about the insurance problem, which had to be solved somehow. My father suddenly said, “Why don't you call Karwecki?” Karwecki was a member of the SPD and only 24 years old at the time, but to me, at fifteen, he was an adult. He was chairman of the Bad Nauheim City Youth Council, which had been founded just a year earlier. 28 My father knew him by chance.

I arranged with him that I would attend a meeting of the board of the Stadtjugendring (City Youth Council) in the Old Town Hall on the market square in Bad Nauheim. There I told them about my plan for the bike trial and my problem with insurance. They immediately agreed to the bike “trail,” as they naturally called it, saying that it would be no problem if I was willing to take on the organizational work and that the insurance would automatically be covered by the SJR! It couldn't have gone better. Now everything happened very quickly. Exactly six weeks after the trial in Mauer, the first bike trial took place in Bad Nauheim on May 25, 1974 (see point 5 “Bad Nauheim - Bike Trial on 25 May 1974").

On the bike

I am adding a few illustrations here that would have disrupted the above presentation, but which perhaps illustrate the situation at that time quite well.

Back then, my bike played an important role in my life. Even the daily ride to school on my “Florian”—always cutting it close, of course—was important to me: it was a wonderful and relaxing contrast to class. At the time, it was completely normal for pupils to ride their bikes to school—the numerous bike racks in schoolyards were always full. What was less normal, it seems, was to use the bicycle for anything other than transportation – in any case, I always wondered why I was apparently the only one exploring the forests around Bad Nauheim by bicycle. The racing bikes and Bonanza bikes that were popular in the 1970s were of course not particularly suitable for off-road riding, but there were still plenty of normal bikes, like the one I had.

Of course, my visits to motorcycle races—which I usually attended on my “Florian”—were an additional inspiration for my cycling activities, and I tried to recreate what I saw on my bike. For “road racing,” the parking lot of the spa hotel, which was almost always empty during the day, offered fast conditions with its tight curves, including a hairpin turn at the end of the parking lot, which you could approach with gusto thanks to the slope of the parking lot. After the hairpin turn, it went uphill again – sometimes I tried riding on the rear wheel. It worked quite well – while sitting. But it didn't make any “sense” to me in terms of learning riding techniques – it was just fun. Once back at the top, I did it all over again, hopefully a tad faster.

I even tried “track racing.” Back then, I was an early riser and full of energy. Morning meadows, still wet with dew and located on slopes, offered the opportunity to drift downhill for surprisingly long distances with enough momentum, by pedaling backwards and tilting the bike slightly. It was also advantageous that there were no off-road tires yet! Of course, the drifting only worked until the momentum was used up, but it felt great (the word “geil” was not yet used in its current meaning).

I took motocross a little more seriously. I chose a circuit at the edge of a gravel pit with downhill and uphill sections, just like real motocross. I also had a steep descent, but I had to make concessions on the uphill sections and I didn't have any jumps, which weren't a given in motocross at that time either. In “MOTORRAD” magazine, I found an advertisement for Husquarna importer and motocross dealer Alfred Krischer, from whom you could order a free “Handbook on modern training methods for motocross riders.” It was a booklet from Husquarna that focused more on gymnastics, strength training, and nutrition than on riding training. Nevertheless, this guide was a contact with the world of racing and an additional motivation to do energy-sapping laps on my “motocross” track with a discarded 28" Dutch bicycle (see text five paragraphs below). It was fun to arrive at the top of the steep descent out of breath and then continue riding without hesitation. The fact that the 28“ Dutch ladies' bike was technically unsuitable for my ”motocross" didn't bother me at all and didn't detract from the fun. I never took any times anyway – what for! Much more important for the riding enjoyment was that I didn't have to be careful with the old bike.

I must mention another “discipline,” a descent that today might be called downhill, but which had no name for me. It is important to know that the contiguous forest area of the Frauenwald and Johannisberg was an extension of the large spa gardens in Bad Nauheim. That is why there are rustic wooden shelters there dating from the time the forest park was created around 1900 – one of them is the Kirchner Hut, near which the first bike trial took place in 1974. In this area, individual, continuous walking paths were graveled to keep them clean and passable even when wet. Since the gravel sank into the ground when wet and had to be replaced repeatedly due to the autumn leaves, these gravel paths were eventually given a solid surface such as asphalt. In combination with a Torpedo three-speed gear shift, it was possible to reach considerable speeds on one of these solid paths, which was about a kilometer long, consistently and almost straight, and led downhill at a considerable gradient.

The highlight was that this forest path was not completely straight and there were also various bumps and a few protruding roots and even tree stumps on this otherwise perfect path, as well as a few small curves that became tight at speed, and a few longitudinal gullies created by rainwater runoff. Above all, however, there were trees everywhere right next to the path and even in the middle of it in one place. You could ride at full speed almost everywhere, but you had to be absolutely focused. At that time, I knew every detail of this frequently traveled path inside and out. It was fun to fly past roots and trees at high speed on the ideal line and aim for the curves. At the time, I considered it to be the closest thing to a (motorcycle) “road race.” I rarely encountered walkers who would have been in my way. After all, you didn't have to race down there on a Sunday afternoon.

I had a second, completely different downhill route in the Frauenwald forest, which was not graveled and less steep. The appeal of this route was that it contained individual cross-country passages as highlights throughout, which contrasted with the otherwise harmless route: hollows, roots, and earth slopes, both uphill and downhill. The crowning glory, which you could look forward to the whole time, was a daring descent on a steep meadow slope at the “Äppelwoitreppchen” immediately after leaving the forest. When wet, this steep slope was impassable because you would have gone much too fast. There were only normal tires, which offered no grip on wet grass. Even in dry conditions, on this descent, which I started very slowly at the top, you would get faster and faster with a locked rear wheel, only to crash into a meadow at the bottom after a bump. This brought the second descent route through the Frauenwald to an abrupt end and gave way to a feeling of satisfaction on the way home.

The descent at Äppelwoitreppchen soon cost me a new fork—the old one had taken a bad knock at the end of the descent and bent backwards. My parents were now worried about my beautiful “Florian,” and I didn't want to ruin it either. The solution was my grandmother's old Dutch bike, which was no longer in use, and one of my classmates also had one lying around. Everything superfluous was removed, and now these bikes had to serve for such undertakings. So now I thundered down the steep descent on the 28“ Dutch bikes (I only ever rode the gravelly, fast route with the ”Florian" because the Dutch bike

without gears, was too slow and the seating position made it no fun to ride) – at least until the steering heads of the two ladies' bikes moved toward the saddle and the pedals got closer to the ground. After that, I got rid of this courage descent bike – it had served its purpose. The cross rounds in the gravel pit also came to an end – from May 1973 onwards, there was only trials riding, which I did with the “Florian.”

Only the rapid descent on the gravel forest path between the trees retained its charm and thrill whenever I passed by, which was quite often, because this descent was a good return route for me and the crowning glory after many off-road tours in the endless forests of the Winterstein area. I would have to take another look at this descent to see if it still looks the same after fifty years or if it has changed significantly. I haven't been there in a long time – the large photo above was taken in 2014 and shows the lower part of this route. The path had been freshly filled with gravel at the time. I had never seen the path in such good condition – I only knew it with a more uneven surface of old, concrete-hard gravel. The condition in the photo is certainly a result of the State Garden Exhibition, which took place in Bad Nauheim in 2010 and revived some of the old spa facilities that had been lying fallow for a long time.

- The five-part article ‘Trials riding – but how?’ by Jürgen Goebel appeared in the following issues of Das MOTORRAD: No. 16 (12 August 1972), pp. 32–33; 17 (26 August 1972), p. 30; 18 (09/09/1972), pp. 32–33; 19 (23/09/1972), p. 51; and 26 (30/12/1972), pp. 32–33. ↩

- MOTORRAD No. 16 (12 August 1972), p. 33 ↩

- MOTORRAD No. 16 (12 August 1972), p. 33 ↩

- All my photos from those years – including those from my first bike trial in 1974 – were taken with this ‘foolproof’ camera, which only allowed you to choose between “sunny” or ‘cloudy’ settings and nothing else. You can recognise these pictures by their square format. ↩

- The photo shows page 32 in the fifth part of the article in Das MOTORRAD No. 26 (30 December 1972), pp. 32–33. ↩

- MOTORRAD No. 12 (16 June 1972), p. 75 ↩

- At the time, I was not aware that Crius originally wanted to write his book ‘only about his own domain in motorcycling, trials riding. But then he was persuaded that trials riding should not be viewed in isolation from all the other disciplines of motorcycling, but rather as one part of the whole – and certainly not the least important part.’ This quote, taken from a review of the first edition of ‘Sport mit Motorrädern’ (Motorcycle Sports) in MOTORRAD (Das MOTORRAD No. 8 (08.04.1967), p. 237), corresponds to the earlier idea that trials, which were held in adverse conditions during the winter months, served as training in balance and reaction for all other racing disciplines that took place during the summer months. ↩

- MOTORRAD No. 15 (29 July 1972), p. 70 ↩

- MOTORRAD No. 21 (21 October 1972), p. 67 ↩

- Crius (Christian Christophe): Sport mit Motorrädern (Motorcycle Sports), Motorbuch Verlag Stuttgart, 3rd edition, 1972, p. 9 ↩

- Crius (Christian Christophe): Sport mit Motorrädern (Motorcycle Sports), Motorbuch Verlag Stuttgart, 3rd edition, 1972, p. 9 ↩

- The reason for this was that trials originated from reliability trials, in which the demands of the course determined whether the machines were up to the task. When better machines were later used on more difficult courses and through sections, and a rider evaluation system was introduced, the old basic approach remained unchanged.

How far is this from the current scoring system in bicycle trials, which seeks to avoid frustration among riders by awarding bonus points and separately evaluating the difficulties in each section, ranked from easy to difficult! This scoring system, which was developed for and is suitable for artificially constructed obstacles, creates a different kind of frustration for participants in natural terrain, as the gates that have to be ridden through in the correct order turn each section into a search game. Above all, however, the layout of sections in natural terrain is made more difficult and also impaired, as the conditions there – unlike artificially constructed sections on the market square or in the hall – cannot be arranged at will. ↩ - At that time, I was also unaware that Crius had been writing for Das MOTORRAD for decades. Further information about him can be found in the article ‘Unser Crius wurde Sechzig’ (Our Crius turned sixty) by Siegfried Rauch, then editor-in-chief of MOTORRAD, who described Crius as a man who was ‘a humorist and philosopher, technician and artist, theorist and tinkerer all rolled into one – and also a motorcyclist – no, a motorcycling enthusiast to the very depths of his being’; Das MOTORRAD No. 24 (23 November 1963), pp. 669–671, quote on p. 669. ↩

- It was a report on the 1962 Clamart Trial near Paris, in which Crius himself had participated. It appeared under the headline ‘Trial Clamart from the handlebars’ in Das MOTORRAD No. 6 (17 March 1962), pp. 24–25, and was reprinted by Crius five years later in expanded form as a subchapter entitled ‘A Trial ... from the Handlebars’ in his book Crius (Christian Christophe): Sport mit Motorrädern (Motorcycle Sports), Motorbuch Verlag Stuttgart, 3rd edition, 1972, pp. 11–17. ↩

- Crius (Christian Christophe): Sport mit Motorrädern (Motorcycle Sports), Motorbuch Verlag Stuttgart, 3rd edition, 1972, p. 16 ↩

- Crius (Christian Christophe): Sport mit Motorrädern (Motorcycle Sports), Motorbuch Verlag Stuttgart, 3rd edition, 1972, p. 17 ↩

- At the time, I wasn't aware of how recent the beginnings of German trials were, even though I had seen that helmets weren't worn in trials and that half-shell helmets were still occasionally worn in motocross. In my later club, MSC Dilltal in Aßlar, there were still one or two homemade Zündapps in the shed – what a great photo opportunity that would have been! The older members of the club still talked about those days now and then. But I was a teenager at the time and thought it was all very distant. Today, I am laboriously trying to catch up with these things. ↩

- Crius (Christian Christophe): Sport mit Motorrädern (Motorcycle Sports), Motorbuch Verlag Stuttgart, 3rd edition, 1972, p. 9 ↩

- MOTORRAD No. 16 (12 August 1972), p. 33 ↩

- You can get an impression of this under point 3 in ‘Ebstorf Bicycle Trials Club (1961-1964)’. The announcement shown there for the second round of the 1970/71 European Trials Championship in Ebstorf on 25 October 1970 was also created in this way. ↩

- FAHRERLAGER 3 (March) 1973, p. 22 ↩

- It was only much later, during my research on this trial, that I learned that this bicycle class in Mittelberg had not been a real trial at all. However, in 1972, there had been a real bike trial organised by the same organiser in Engabrunn, about ten kilometres away – see point 4, ‘“Bicycle Trial Engabrunn (1972)”'. ↩

- This applies to all issues of FAHRERLAGER since its inception – at least if one disregards the article ‘How to win Trials’ by Sammy Miller, which appeared in the British magazine MOTOR CYCLING on 2 February 1961 and was translated into German in FAHRERLAGER No. 4 (April) 1961 (pp. 2-4). In this translation, ‘Wie man Trials gewinnt’ (How to win trials), it said (p. 4): "Looking back on my school days, I realise how much I owe to the bicycle (...) There is no better preparation (for trial riding) than trick riding on a bicycle, because it sharpens your sense of balance and handling." To what extent was the Ebstorf Bicycle Trial Club in 1961 encouraged and inspired by these words of Sammy Miller in FAHRERLAGER? ↩

- FAHRERLAGER No. 10/73 (November), pp. 3–4 ↩

- FAHRERLAGER No. 11/73 (December), pp. 6–7. The book was first published in 1969 and reprinted in 1971. ↩

- Forty-six years later, I rediscovered this cut with its six sections that had so thrilled me back then – what a great experience! TRIALSPORT No. 540 (March 2021), pp. 52–61, features a report by Hans Greiner about this reunion, including several photos. ↩

- FAHRERLAGER 2/74 (February/March), p. 21 ↩

- Rolf Karwecki (1950-2018) later became mayor of the municipality of Habichtswald and was a member of the Hessian state parliament for ten years. A few years ago, I wanted to tell him what had become of ‘his’ bicycle trial organised by the Bad Nauheim City Youth Council, but it was too late: while researching him, I learned that he had already passed away. There is a Wikipedia page about him: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rolf_Karwecki ↩